Getting Started with CTEM

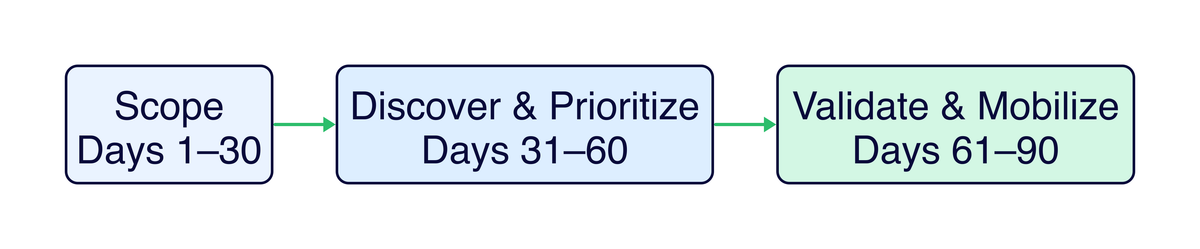

Goal: Run one complete CTEM cycle in 90 days. Prove the model works with measurable exposure reduction on a specific attack surface. Expand from there.

Most organizations stall on CTEM because they try to operationalize it as a program before proving it works as a project. This guide treats your first cycle as a time-boxed pilot: narrow scope, concrete deliverables, and a clear decision point at day 90 about whether (and how) to expand.

This is not a tool selection guide or a maturity model assessment. It's the operational sequence for running a single CTEM cycle end to end, written for the person who will actually do the work.

Figure 1: A 90-day CTEM pilot broken into three phases. The timeline is aggressive by design. Constraint forces focus.

Before You Start: Readiness Signals

Skip the checklist of obvious prerequisites. Instead, answer these honestly. They predict whether your pilot will produce results or stall out.

Can you name the engineering team that will fix what you find?

This is the single highest-signal readiness indicator. CTEM's value is realized in remediation, not discovery. If you don't have a specific team (with a specific lead) who will implement fixes on the assets you're scoping, you don't have a CTEM pilot. You have a report that will sit in a queue.

If you can't name them: Start there. Pick a scope where you already have engineering rapport. The identity team that's been responsive on access reviews, or the platform team that co-owns the cloud environment with you. Build the pilot around a scope they care about too.

Does your sponsor understand this is a cross-functional program?

An executive who says "go do CTEM" but expects it to stay within the security team's ticketing system will create a ceiling at validation. The sponsor needs to be willing to broker conversations with engineering leadership about remediation SLAs, not just approve your project charter.

Test this early: Present a hypothetical scenario: "We find a critical exposure in production that requires a config change by the platform team during their sprint. How do we get that prioritized?" If the answer involves escalation paths that actually exist, you're in good shape.

Do you have access to the data you'll need for your scoped domain?

Not "do you have an asset inventory" (you probably don't have a complete one, and that's fine). The question is: for the domain you're scoping, can you actually query the systems that hold the truth?

| If your pilot domain is... | You need access to... |

|---|---|

| External attack surface | DNS records, cloud console, certificate transparency logs, WAF/CDN configs |

| SaaS posture | Admin consoles for in-scope tenants, OAuth app registries, IdP integration configs |

| Identity pathways | IdP/directory, PAM platform, cloud IAM policies, group membership data |

If getting read access to these systems will take more than a week of approvals, factor that into your timeline or pick a different scope.

What NOT to do (and why programs actually fail)

- Don't scope broadly to "show value." Broad scope in cycle one produces a large, low-confidence exposure list that overwhelms remediation capacity. Nobody acts on a 400-item backlog they didn't ask for. A narrow scope that results in 15 validated, remediated exposures will do more for your program than a broad scope that produces 400 unvalidated findings.

- Don't select tools before you understand your workflow. Tool selection is a Phase 2 concern at earliest. For a pilot, you can run discovery with existing scanners, cloud console queries, and manual review. Teams that start with tool procurement spend 60+ days on evaluation and never reach validation.

- Don't treat validation as optional. The instinct is to skip from prioritization to remediation ("we found a critical CVE, just patch it"). Validation is where you differentiate CTEM from vulnerability management. It answers whether the exposure is actually reachable and exploitable in your environment, which changes remediation priority in roughly 30-40% of cases.

Phase 1: Scope (Days 1-30)

Scoping is the most important stage and the one teams skip most often. Teams rush through it because it feels like overhead, but poor scoping is the primary reason CTEM pilots produce noise instead of signal.

Week 1-2: Select your pilot domain

Choose based on three criteria, not just "what seems important":

1. Where do you have remediation capacity? Pick a domain where the team responsible for fixes has bandwidth and willingness. A perfect scope that lands in a team buried in a platform migration will go nowhere.

2. Where is the exposure data accessible? Choose a domain where you can actually enumerate assets and exposures without a multi-month data integration project. If your cloud environment has good API coverage and your SaaS tenants have admin console access, those are better pilot candidates than an on-prem environment where asset data lives in disconnected spreadsheets.

3. Where can you demonstrate business-relevant risk reduction? The pilot needs to produce results your sponsor can communicate upward. "We reduced admin interface exposure on the customer portal from 4 reachable paths to 0" is more compelling than "We found and patched 12 CVEs across miscellaneous internal systems."

| Pilot domain | When it works well | When it doesn't |

|---|---|---|

| External attack surface → specific application | You have internet-facing services with clear ownership and a responsive platform team | The application is maintained by an outsourced team with 30-day change windows |

| SaaS posture for a critical tenant | You have admin access, the SaaS platform has decent API/config visibility, and the business unit is engaged | The tenant is managed by a business unit that views security as interference |

| Identity pathways to privileged roles | Your IdP/PAM tooling provides good visibility, and the identity team is a willing partner | Privileged access is fragmented across 5 systems with no central visibility |

The best pilot domain is often not the one with the highest risk. It's the one where you can execute a full cycle. A completed pilot on a moderate-risk domain builds the credibility and muscle memory to tackle the high-risk domain in cycle two. A stalled pilot on the highest-risk domain builds nothing.

Week 3-4: Write the scope charter

The scope charter is a forcing function. Writing it surfaces gaps in your thinking that are invisible when the scope lives in your head. Keep it to one page.

The non-obvious elements that separate useful scope charters from performative ones:

Threat scenarios, not just asset lists. "Customer portal is in scope" is an asset list. "External attacker with stolen customer credentials attempting to pivot to admin functionality" is a threat scenario. The scenario determines what exposures you look for during discovery. Without it, discovery becomes unfocused enumeration.

Explicit exclusions with reasoning. "Internal corporate IT is out of scope because it's a separate risk domain with different ownership" is useful. Exclusions without reasoning invite scope creep when someone asks "but what about...?"

Success criteria that aren't circular. "Reduce critical exposures" is circular (you're defining success as doing the thing you set out to do). Better: "Eliminate all internet-reachable paths to the admin interface" or "Reduce the number of accounts with standing privileged access to production from 47 to under 10." Specific, verifiable, and tied to a meaningful risk reduction.

Example scope charter:

CTEM Pilot Cycle 1: External Attack Surface → Customer Portal

In Scope:

- portal.example.com and all subdomains

- APIs serving the portal (api.example.com/v2/*)

- Authentication pathways (SSO integration, MFA enrollment, session management)

- Admin interfaces for portal management (admin.example.com)

- DNS records and certificate configurations for above

Out of Scope:

- Internal corporate IT (separate risk domain, different remediation team)

- Marketing website (static content, minimal attack surface, separate ownership)

- Mobile applications (planned for cycle 2 pending API exposure findings)

Threat Scenarios:

1. External attacker using commodity tooling against internet-facing services

2. Attacker with stolen customer credentials attempting privilege escalation

3. Attacker targeting admin interfaces via exposed or guessable endpoints

Success Criteria:

- Zero internet-reachable admin interfaces without MFA + IP restriction

- All P1 exposures validated and remediated or risk-accepted with documentation

- Every in-scope asset has an assigned owner in the exposure register

- Mean time from P1 validation → remediation ticket < 48 hours

Timeline: 90 days (March 1 – May 30)

Sponsor: [CISO]

Operator: [You]

Engineering Partner: [Platform team lead]

Escalation Path: [Sponsor → VP Engineering for remediation blockers]

Phase 2: Discover & Prioritize (Days 31-60)

This phase is where most teams either produce the evidence base that drives action or generate a pile of findings that overwhelm everyone. The difference is discipline about what you collect and how you structure it.

Week 5-6: Build the asset inventory for your scoped domain

You're not building an enterprise asset inventory. You're building a scoped, evidence-based view of what exists within your pilot domain. The goal is coverage within scope, not completeness across the enterprise.

For each asset, capture four things:

| Field | Why it matters | How to get it |

|---|---|---|

| Asset identifier | You need to reference it unambiguously | DNS, cloud resource ID, URL, service name |

| Owner (team + individual) | Remediation requires a human to act | Cloud tags, service catalog, ask the platform team |

| Business criticality | Prioritization depends on blast radius | Talk to the application owner. Don't guess from infrastructure metadata. |

| Exposure posture | Internet-facing vs. authenticated vs. internal changes everything | Network config, WAF rules, cloud security groups |

Discovery feels productive. You're learning things, your spreadsheet is growing, you're finding assets nobody knew about. But discovery without a stopping condition becomes its own project. Set a hard boundary: at the end of week 6, you work with what you have. Gaps in your inventory become findings themselves ("we cannot determine ownership of 3 subdomains" is a valid P2 exposure).

Where teams actually get stuck:

- Ownership gaps. ~20-30% of assets in a typical pilot will have unclear ownership. Don't let this block you. Flag "owner unknown" as an exposure (it is one; unowned assets don't get patched) and assign a temporary owner from the platform team for the purposes of this cycle.

- Data fragmentation. Asset data lives in DNS, cloud consoles, IdP, service mesh configs, CI/CD pipelines, and someone's head. For a pilot, manual correlation is fine. If you need to query 4 systems and cross-reference in a spreadsheet, that's a valid approach for cycle one.

Week 7-8: Enumerate and prioritize exposures

Layer exposure data on top of your asset inventory. For each in-scope asset, ask: what weaknesses exist, and how reachable/exploitable are they?

Exposure sources to query (for your scoped domain, not everything you own):

| Source | What you're looking for | Non-obvious gotcha |

|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability scanner | CVEs on in-scope assets | Scanner coverage gaps are exposures themselves. If your scanner doesn't cover 3 of 12 in-scope services, that's a finding. |

| Cloud security posture | Public exposure, overly permissive policies, missing encryption | "Compliant" doesn't mean "not exposed." A security group that allows 0.0.0.0/0 on port 443 is compliant with many benchmarks but creates reachability. |

| Identity platform | Privileged accounts, stale credentials, MFA gaps, OAuth grants | Focus on standing access to in-scope assets, not enterprise-wide identity hygiene. |

| DNS / certificate transparency | Unexpected subdomains, dangling CNAME records, expiring certs | Dangling DNS records are often overlooked but enable subdomain takeover, which is a validated P1 in many environments. |

| Code / secret scanning | Hardcoded credentials, API keys in repos related to in-scope services | Scan commit history, not just current HEAD. Rotated secrets in git history are still exposed if the repo is accessible. |

Prioritize: the part that separates CTEM from vulnerability management

CVSS alone is a severity score, not a risk assessment. A CVSS 9.8 on an internal-only, non-production system behind a VPN with no sensitive data is genuinely less urgent than a CVSS 7.0 on your internet-facing authentication service.

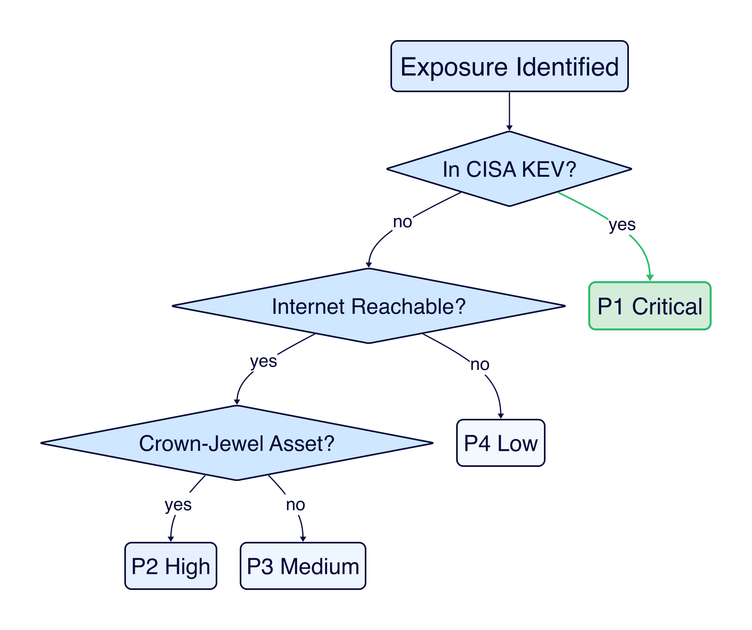

Figure 2: A simplified prioritization decision tree. KEV status is the fastest signal; reachability and asset criticality determine the remaining triage.

Practical prioritization for a pilot (keep it simple, make it defensible):

| Priority | Criteria | What makes it this priority | Target SLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 - Critical | Actively exploited (in CISA KEV) OR internet-reachable + known exploit + crown jewel asset | Attacker can realistically reach and exploit this now, and the impact is material | 7 days |

| P2 - High | Reachable + high severity + business-critical asset, but no known active exploitation | Exploitable attack path exists but requires more attacker effort or sophistication | 30 days |

| P3 - Medium | High severity but limited reachability, OR strong compensating controls in place | Risk exists but the path requires chaining multiple weaknesses or bypassing working controls | 60 days |

| P4 - Low | Low reachability + low impact, or theoretical risk only | Not actionable in this cycle. Document and revisit if reachability changes. | Accept or defer |

The prioritization decisions that actually matter:

- Downgrading based on compensating controls requires evidence, not assumptions. "The WAF should block this" is an assumption. "We tested this exploit against the WAF and confirmed it blocks the payload" is evidence. If you haven't validated the control, don't use it to downgrade.

- Ownership unknown = P2 at minimum. An unowned asset with any exposure is higher risk by default. Nobody is monitoring it, patching it, or responding to incidents on it.

- EPSS > CVSS for exploit probability. FIRST's EPSS provides a 30-day exploitation probability estimate that's more predictive than CVSS severity for determining which vulnerabilities attackers actually target.

Phase 3: Validate & Mobilize (Days 61-90)

Validation is where CTEM earns its keep. Without it, you're running a vulnerability management program with better prioritization. That's an improvement, but not the structural shift CTEM promises.

Week 9-10: Validate P1 and P2 exposures

Validation answers two questions that scanning cannot:

- Can an attacker actually exploit this in our environment? (Not "is there a CVE" but "does the exploit work against our config, our WAF, our network segmentation?")

- Do our defensive controls detect and respond to this? (Not "do we have a WAF" but "does the WAF block this specific attack? Does the SOC see it? What's the response time?")

Validation methods, matched to exposure type:

| Exposure type | Validation approach | What "validated" means |

|---|---|---|

| CVE on internet-facing service | Confirm version, test exploit in staging or with safe PoC, check WAF/IPS behavior | "We confirmed the service runs version X.Y, the exploit succeeds against it, and the WAF does not block the payload" |

| Misconfiguration (cloud/SaaS) | Verify current config state, test whether the misconfiguration enables the predicted access | "The S3 bucket policy allows public read. We confirmed unauthenticated access to objects containing [data type]" |

| Identity/access weakness | Confirm current auth requirements, test privilege escalation or lateral movement path | "An account with [role] can escalate to [privileged role] via [mechanism] without triggering any alert" |

| Exposed admin interface | Test reachability from external/untrusted networks, verify authentication and logging | "admin.example.com is reachable from the internet, accepts password-only auth, and no login attempts appear in SIEM" |

A pentest is an open-ended assessment. Validation in CTEM is targeted: you have a specific exposure, a specific hypothesis about whether it's exploitable, and you test that hypothesis. Faster, cheaper, and directly useful for remediation decisions. Most P1/P2 validations take hours, not weeks.

What validation changes:

- ~30-40% of P1/P2 exposures will be downgraded after validation (compensating controls work, the exploit doesn't apply to your config, the asset isn't actually reachable via the path you assumed).

- ~10-15% will be upgraded (the exposure is worse than the scanner indicated, or the compensating controls don't actually work).

- The remaining items proceed to mobilization with evidence that compels action.

Week 11-12: Mobilize remediation

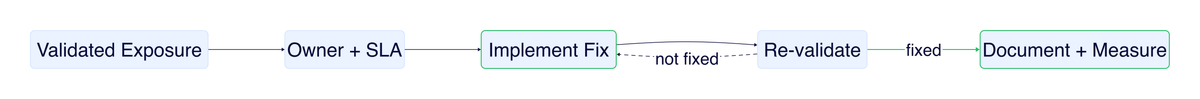

Figure 3: Validated exposures follow a closed-loop workflow: assign, fix, re-validate, document. Findings that aren't actually fixed don't get closed.

Mobilization is where CTEM programs succeed or die. Discovery and validation are security activities. Mobilization is a cross-functional operational workflow. The quality of your remediation tickets directly determines whether engineering acts on them or ignores them.

What a mobilization-quality finding looks like vs. what engineering ignores:

| Field | What engineering ignores | What drives action |

|---|---|---|

| Title | "Critical vulnerability CVE-2024-XXXX" | "Internet-reachable RCE on portal API, validated exploit, no WAF coverage" |

| Evidence | "Nessus plugin 12345 flagged this" | "We confirmed exploitation against staging on [date]. WAF rule set does not cover this payload. Screenshot/logs attached." |

| Recommended fix | "Apply vendor patch" | "Upgrade library X from 2.1.3 to 2.1.7. Alternatively, add WAF rule [specific rule] as interim mitigation. Here's the config diff." |

| Impact if not fixed | "CVSS 9.8" | "An external attacker can achieve RCE on the portal API server, which has read access to the customer database (450K records). No compensating control prevents this." |

| How to verify | (not included) | "After patching, re-run [specific test] and confirm the endpoint returns 403 instead of 200." |

Removing friction from remediation:

- Pre-approve change windows for P1 items with your sponsor before you need them. The worst time to negotiate emergency change authorization is during the emergency.

- Pair with engineering on the first fix. Don't throw tickets over the wall. Sit with the engineer implementing the first P1 fix. You'll learn how they think about the problem, they'll learn what validation evidence looks like, and subsequent fixes will go faster.

- Escalation paths must exist before you need them. Document: "If a P1 remediation is blocked for >48 hours, [sponsor] escalates to [VP Engineering]." If this path doesn't exist, negotiate it during scoping.

Week 12: Verify and close the loop

- Re-validate every fixed exposure. Run the same test that proved exploitability. If the fix works, the test should fail. If it doesn't fail, the fix didn't work. Send it back.

- Calculate exposure reduction. Raw numbers: "We started with X P1/P2 exposures. Y are remediated and re-validated. Z are risk-accepted with documentation. W remain in progress."

- Document what you learned for cycle 2. Not a formal retrospective document. Just a short list: what slowed you down, what worked, what you'd scope differently.

Metrics That Matter

For the pilot: prove the model produces outcomes

| Metric | What it actually tells you | Target for cycle 1 |

|---|---|---|

| P1 exposures remediated / total P1 | You can close critical gaps through this workflow | >90% remediated or risk-accepted |

| Median days: P1 discovery → remediated | The operational pipeline is fast enough to matter | Under 14 days |

| Exposures downgraded after validation | Validation is saving remediation effort (proving its value) | 25-40% of initial P1/P2 list |

| % of in-scope assets with assigned owner | You can actually mobilize | 100% |

| Exposure count trend across the 90 days | Net risk is decreasing, not just being discovered | Downward after day 60 |

Metrics that indicate your program is working vs. just running

- Remediation re-open rate. If >20% of "fixed" exposures fail re-validation, your fix quality is too low. Engineering needs better guidance, or the fixes are being done superficially.

- Time from validation → ticket creation. If this exceeds 5 business days, you have a mobilization bottleneck. Validation evidence is losing urgency while sitting in a queue.

- P1 exposures discovered in cycle 2 that existed in cycle 1 scope. If you're finding P1s in the same scope area, your discovery or remediation in cycle 1 had gaps.

Metrics to avoid

- "Total findings discovered": Volume is not value. A large number can mean poor scoping, noisy tooling, or both.

- "Number of scans completed": Activity, not outcome. Nobody's risk posture improved because you scanned more.

- "Tickets created": Work generated is not work completed. Track remediation completion and re-validation pass rate instead.

After Day 90: Expanding the Program

The cycle 2 decision

At day 90, you have enough data to make three decisions:

-

Should we run another cycle? If you successfully reduced P1 exposures and the workflow produced remediation (not just reports), the answer is almost certainly yes. Present the results to your sponsor with a recommendation for cycle 2 scope.

-

What scope for cycle 2? Two options:

- Same scope, deeper. Go back through the same domain with improved discovery (you know where the gaps were) and tighter SLAs. Good if cycle 1 revealed significant discovery gaps or remediation was incomplete.

- Adjacent scope. Expand to a related domain (e.g., if cycle 1 was external attack surface for the customer portal, cycle 2 adds the identity pathways that authenticate to it). Good if cycle 1 was clean and you want to broaden coverage.

-

What investment is needed? Cycle 1 ran on manual effort and existing tools. Cycle 2 is where you make evidence-based tool decisions: "Discovery took 40 hours of manual work in cycle 1. An EASM tool would reduce that to 4 hours and provide continuous monitoring." That's a concrete business case, not a speculative tool purchase.

Increasing cadence

- Cycle 1: 90 days (quarterly). Proving the model.

- Cycles 2-3: 60 days. Process is established, discovery is faster with lessons learned.

- Steady state: Monthly scoping reviews, continuous discovery, validation triggered by material changes (new deployments, new threat intel, KEV additions).

Building continuous validation

The highest-leverage investment after cycle 1 is making validation less manual:

- Automated checks for known exposure patterns (e.g., "is admin.example.com reachable from the internet?" as a recurring test)

- Integration with deployment pipelines (new deployments trigger exposure checks against the scoped domain)

- Attack path analysis tooling to maintain a current view of reachability without manual testing

Practical Questions

"We have 6 scanners already. Why isn't that CTEM?"

Scanners produce findings. CTEM produces remediated exposures through a structured workflow. The difference is in what happens after discovery: prioritization that accounts for business context and reachability, validation that proves exploitability, and mobilization that drives fixes to completion. If your scanners produce reports that sit in a queue, adding a 7th scanner won't help.

"How do I get engineering to actually fix what we find?"

The framing matters more than the escalation path. "You have 47 critical vulnerabilities" triggers defensiveness. "We validated that an external attacker can reach the customer database through this specific path, and here's the evidence" triggers action. Lead with the business impact and the validation evidence, not the finding count. And include the fix. Engineers respond to "here's what to change" better than "here's what's broken."

"What if our asset inventory is terrible?"

Good, that's honest. Building a scoped inventory is part of Phase 2, and the inventory only needs to cover your pilot domain. Start with what you can programmatically query: DNS zone files, cloud resource APIs, IdP application registries. Cross-reference with the team that runs the scoped services. A complete-for-scope inventory built in 2 weeks is better than waiting 6 months for an enterprise-wide CMDB project.

"Should we hire a CTEM analyst or buy a CTEM platform?"

Neither, for cycle 1. Run the pilot with an existing team member (~0.5 FTE for 90 days) and existing tools. After cycle 1, you'll know exactly where the manual effort concentrated and what tooling would reduce it. You'll also know what workflow your organization actually follows, which is the only way to evaluate whether a platform fits. Platform purchases made before running a cycle almost always require significant rework once the operational workflow becomes clear.

"What if our remediation takes longer than the SLAs?"

Track it, escalate it, and don't hide it. If P1 remediation consistently takes 30 days instead of 7, that's the most important finding of your pilot. Not the exposures themselves, but the operational inability to fix critical issues quickly. Surface this to your sponsor as a systemic risk: "Our mean time to remediate internet-facing critical exposures is 30 days. During that window, we are knowingly exposed." That data drives investment in remediation capacity better than any vulnerability report.

"How does this relate to the five CTEM stages?"

This guide compresses the five stages into three operational phases for a 90-day pilot. Phase 1 (Scope) maps directly to the Scoping stage. Phase 2 combines Discovery and Prioritization. Phase 3 combines Validation and Mobilization. As your program matures, each stage gets its own cadence and dedicated attention.

Resources

- The Five Stages of CTEM: detailed guidance for each stage of the lifecycle

- CTEM vs Vulnerability Management: why CTEM is a structural shift, not just "better VM"

- CTEM vs Exposure Management: how CTEM relates to the broader discipline

- CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog: the most useful exploit evidence for prioritization

- FIRST EPSS: exploit probability scoring for data-driven prioritization

- CTEM Identifier Catalog: standardized exposure types for consistent classification

- Join the Working Group: contribute to the open standard